Archive for November, 2009

The Slugger O'Toole Awards – blogs and politics

Tim McGarry at the Slugger Awards

Tonight in Belfast, we’re running the second in what I hope will become the annual ‘Slugger Awards‘.

These awards – previewed here on the Amnesty blog – are something of a departure for political weblogs. It would be fair to say that politicians are – for the most part – less than thrilled by the way that blogs have transformed politics.

The Slugger Awards are something of an attempt to redress the balance. Slugger is unusually visible in Northern Ireland’s politics. It has over 34,000 unique visitors per month and Stratagem/ComRes polling shows that 96% of NI Assembly Members read it.

Local democracy and the strange case of speed humps and 20 mph zones

Speed humps: love ‘em or hate ‘em, here in the UK they’ve become a symbol of the traffic calming zeitgeist.

Speed humps also pose a major challenge for local democracy. That’s because local authorities are legally hampered from taking full account of the commonly held view that whilst speed reduction is good, speed humps are bad.

Here’s where I’ve got to in understanding why (stick with me please: it’s also about consultation, deliberative democracy and the Sustainable Communities Act).

A lot of people like the idea of slowing traffic to 20 mph in residential areas (in a 2005 survey cited in a study for Transport for London, 75% of the British public supported 20 mph speed restrictions in residential areas). Less noise, less antisocial car-driving behaviour, less road-rage, reduction of casualties from road traffic accidents, and encouragement (perhaps) for people to leave their cars take to public transport.

All this has helped 20 mph zones to sweep across the country. The London Borough of Southwark (where I live) aims to make 20mph the default speed limit across the entire borough. This sounds good to me.

But this is the problem. It would appear that 20 mph zones cannot, by law, effectively be implemented unless ‘self-enforcing’ traffic calming measures are adopted at the same time. In other words, you can’t have a 20 mph zone unless you simultaneously accept measures like chicanes, speed cushions, speed humps, raised tables, pedestrian islands and the like.

As a (former) lawyer, and therefore something of a nerd about rules, I wanted to know why I kept coming across this argument. In fact, that I’m aware of it at all is down to the e-democracy practised on the East Dulwich Forum where local councillors interact with a very active local community. (Sadly that’s not the ward I live in or my rapidly developing views about 20 mph zones might not have ended up here!)…

Eventually I found the legal answer I was looking for. And it’s clear that it perplexes even experts working within local authorities. For the legal reason that you can’t have a 20mph zone without lumps in the road lies buried in regulations governing the use of traffic signs.

The way this works is that The Traffic Signs Regulations and General Directions 2002 say that a 20mph zone sign “may only be placed on a road if no point on any road (not being a cul-de-sac less than 80 metres long), to which the speed limit indicated by the sign applies, is situated more than 50 metres from a traffic calming feature”. And then the Regulations go on to list the traffic calming features.

Innocent, isn’t it?

But the result is that the real choices offered to people consulted on 20 mph zones are about the kind of self-enforcing traffic calming measure proposed (e.g. whether it should be a hump or a cushion). In contrast, often what people (including me) want to support is the effective enforcement of a 20 mph speed restriction, not the humps and cushions.

Speed cameras and interactive speed signs aren’t an option in a 20 mph zone since they’re not self-enforcing. Consultation responses that request them instead of cushions, humps and the like are therefore likely to be treated as irrelevant.

This poses major problems for public consultation, since unless extraordinarily good practice is followed; deliberative democracy even; it’s unlikely that people will realise what they’re being consulted on.

If you like the idea of a 20mph zone but hate the idea of speed humps, cushions, chicanes and the like, you’re on a hiding to nothing. But it must be unusual for residents to be told that in advance, or to be involved in decisions on what the alternatives might be before consultation on a specific traffic calming proposal linked to 20mph zone starts.

The other problem is simply the conflicting evidence on the pros and cons of speed humps and cushions and the complex balancing acts. Hump-topped ones seem more effective; but they cause greater problems for emergency vehicles and buses. Flat-topped ones don’t work as well, but people on busy roads (which need the speed restriction more) might end up with them because such roads are more likely to be used regularly by buses and emergency vehicles. Etc. If you’re fascinated by this, please see this report from Transport for London, by way of just one of many examples of relections on the subject.

This is a classic situation where deliberation, based on the full range of facts, is more likely to generate consensus. And lack of deliberation dissent.

The Department for Transport notes that: “The value of adequate consultation being undertaken cannot be over-emphasised. Without such consultation, schemes are likely to be subject to considerable opposition, both during and after implementation”. Indeed. Barnet borough council has had a policy of reviewing and possibly removing previously installed speed humps for some years.

For the time being I shall be responding to my current local consultation to say that I’m in favour of the new 20 mph zone that’s been proposed where I live, but not to the use of speed humps and cushions and other so-called ‘vertical deflections’ to enforce it.

In my case this is partly a nimby (‘not in my back yard’) response to extra vibration and possibly extra noise caused by having one directly outside my house. Not just that though: if I thought they’d work it’d be great. I don’t drive and I dislike speeding. But I’m convinced, by credible evidence from Southwark Living streets in particular that humps and cushions generally don’t work very well in my bit of London.

One street where a close friend lives is down to get a sinusoidal hump (why local authorities go out to public consultation using words like ‘sinusoidal’ without further explanation is beyond me). It’s a very short street which ends with a right angle turn up a hill. It would be almost impossible to speed up or down it if you tried. But presumably this and other streets (such as one which already has a speed camera) have to receive ‘self-enforcing’ traffic calming features because otherwise they can’t form part of the 20mph zone.

What I want to be asked is whether I support effective enforcement of a 20mph speed limit in my neighbourhood (I do). And then I want a proper deliberative process about the options so that I understand why it’s really necessary if I do end up with a speed cushion outside my house. But that’s not the question on the table.

What we’ve been asked is not ‘do you want a 20mph speed limit in the zone shown on the attached map’ but ‘do you want a 20mph zone’. Legally there’s a difference; and the difference determines how my view gets counted. It’s obvious isn’t it? Um, not.

Ah; legalistic hairsplitting that only a nerd would get excited about.

The majority of people whose views, like mine, can’t count are likely to feel frustrated and alienated by the Council. My own frustration is partly directed at the Council for not giving us residents the full facts when they consult. But it’s also got a legal outlet; a bigger target to blame. So that’s comforting.

Now a council could in principle impose a 20 mph speed limit without ‘self-enforcing’ traffic calming measures (at least I think it can; I’m not sure how it works in London); but that hasn’t been proposed in my neighbourhood; it’s very unlikely that it will emerge as an option out of consultation because people haven’t been told it might be an alternative; and anyway 20mph speed limits without additional ‘self-enforcing’ traffic calming are recommended by the Department of Transport only for use on roads where average speeds are already below 24mph (definitely not the case on my street save for when it’s too congested for cars to move).

Essentially ordinary 20 mph speed limits rely, like most others, on police enforcement. And the police may have better things to do than deal with calls about speeding cars in an area with a 20 mph speed limit, runs the argument.

Anyway, it doesn’t matter whether you agree with my specific views on speed cushions. The wider issues here are about deliberation and consultation.

Still, if you do happen to agree with me that speed cushions and humps really aren’t the best thing since sliced bread…. could this be an area where people should ask for their local authority to get new powers under the Sustainable Communities Act?

Then local authorities could adopt 20mph zones (not just limits), complete with signs, and experiment with alternative approaches to enforcement that don’t rely on speed humps, cushions and the like. Many residents would thank them; at least if there were good ideas on workable alternatives that didn’t involve citizens’ vigilante speeding patrols.

Might it be worth a coordinated effort if there’s another round of proposals under the Act to ensure that at least one such proposal gets through to the Act’s ‘selector’?

Long live localism and the ‘duty to involve’.

Democratic, decentralised and difficult

I attended an interesting seminar yesterday afternoon, hosted by the 2020 Public Services Trust. The topic was the future of citizen-centred public services.

The two principal speakers both brought innovative ideas and a real vision, which is more than can be said for a lot of these public policy seminars. Ben Jupp, from the Cabinet Office, and Christian Bason from the Danish reform institute Mind Lab, set out a vision that I might crudely summarise as:

- We need to understand that public service goes wider than the things funded or provided by the state – in other words, the hospice movement is part of the health service, even if it isn’t part of the National Health Service

- We need to combine greater user empowerment, productivity drives and a better understanding of user pathways to identify waste in the system

- Future services will be provided in a radically decentralised way – well below town hall level

- Citizen/citizen and citizen/state relationships are the most important element of this new mode of public service

There’s a lot to like in this vision of decentralised, democratic public service, particularly if it brings about the alchemical “better services at lower cost” that we’re all hunting around for.

I don’t think it’s a simple or risk-free transformation, though. The questions that occurred to me were:

- Public service delivery is something that goes wider than taxpayer funding, but it is also something that is fundamentally political. How can decentralised local organisations be made accountable and representative to their users and those who pay any taxes that fund them?

- Are we acknowledging the problems of Whitehall managerialism only to create them over again at local level?

- How do we create the active and informed citizens needed to co-create and co-produce these services? It feels like the change needed – though a good change – is either a years-long cultural transformation programme, or devolution to a group of super-engaged people running local services.

I don’t have any easy answers. I want to see more democratic and less managerial service delivery – which is what both Ben and Christian were describing. I want fair and comprehensive public services. I buy the vision and the potential. My only nagging worry is that in a world where we’re living with the consequences of the efficient markets fallacy, we should be wary of stumbling into an efficient citizen fallacy.

Active citizens, subjective well-being and Clarksonism

Jeremy. Suffering in silence, as ever.....

If you were to add one blog to your RSS reader at my request, please make it Chris Dillow’s Stumbling and Mumbling.

It’s about ‘Clarksonism.’ Why tedious self-pitying rich white blokes on the telly the question of ‘subjective well-being’ is an important one to understand and why politicians often end up being forced to expend lots of energy on people with imaginary grievances while ignoring those with genuine ones:

“Almost a fifth of the poorest one-fifth of people – and these, remember, are the poorest in the world – say they are satisfied with their lives, whilst a third of the best-off fifth say they are dissatisfied.

This suggests that subjective indicators – how people feel, what they say – are an imperfect measure of actual inequality.”

This is another example of the way that highly visible citizens can often dominate debate at the expense of other – perhaps more deserving – cases. In another example of this, the Freethinking Economist gives us Theodore Dalrymple. It is the Jeremys, the Theodores and the Victors who are often – as Anthony observed here a while ago – the main beneficiaries of a good deal of outreach and consultation work.

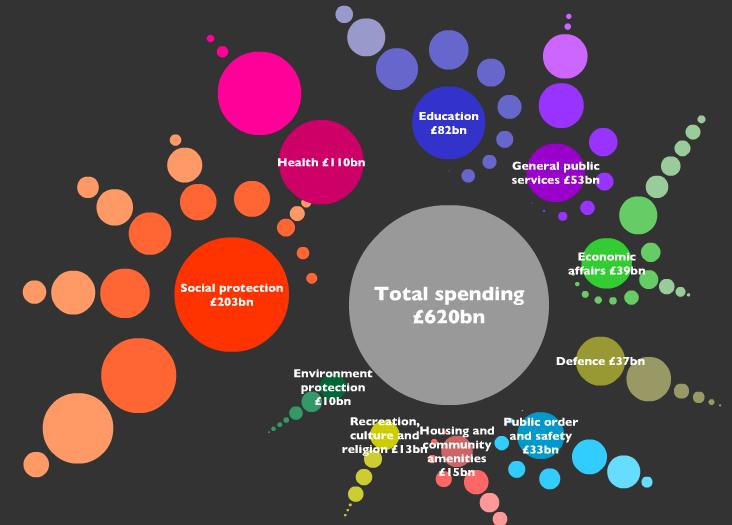

Visualising public spending

Further to the occasional series here looking at ways that people are using open data and visualisation tools to help clarify complex issues, here is the ‘where does my money go‘ application:

The authors say that it’s not finished yet and you can look at their underlying data – they’re looking for feedback.

The authors say that it’s not finished yet and you can look at their underlying data – they’re looking for feedback.

In terms of the delivery, for an alpha release, it’s very good. My minor beef is the same one that I have with ‘They Work For You’ – the notion that politicians work for us, or that government spending represents ‘spending our money’ is on that is allowed to go unchallenged too often. Framing an argument along these lines is, however, a good weekend’s work at least.

The myth of easy engagement: Evans’ Law?

Just a quick response to Tim Davies’ verygood post about ‘The Myth of Easy Engagement’.

There is one argument that supports his general position that, I think, he misses. I’m sure that sooner or later, some will come up with a frivolous law (like ‘Godwin’s Law‘ or ‘Muphry’s Law‘) but if they don’t, let me dibs it:

Evans’ Law

The value of anyone’s opinion is in inverse proportion to their willingness, ability and opportunity to express it effectively.

I think that I’ve outlined this argument here, here, here and here already so I won’t bore you with it again. Chris Dillow has covered it nicely here as well.

Poppies and public consent

Not directly related to local democracy, I know, but I’ve written a post here on Slugger O’Toole responding to an Irish republican about how far the wearing of a poppy can be seen as an endorsement for the actions of the British state.

Not directly related to local democracy, I know, but I’ve written a post here on Slugger O’Toole responding to an Irish republican about how far the wearing of a poppy can be seen as an endorsement for the actions of the British state.

It raises important questions about the legitimacy of democracy and I hope you find it interesting.

Should local authorities subsidise independent local newspapers?

In today’s Guardian, (and here with footnotes) George Monbiot asks:

“I can think of only two local newspapers that consistently hold power to account: the West Highland Free Press and the Salford Star. Are any others worth saving? If so, please let me know.”

His observation ….

“Most local papers exist to amplify the voices of their proprietors and advertisers and other powerful people with whom they wish to stay on good terms. In this respect they scarcely differ from most of the national media. But they also contribute to what in Mexico is called caciquismo: the entrenched power of local elites. This is the real threat to local democracy, not the crumpling of the media empires of arrogant millionaires.”

… is strikingly similar to Helen Swaffer’s line that…

“Freedom of the press in Britain is freedom to print such of the proprietor’s prejudices as the advertiser’s won’t object to.”

In no lesser a place than the Washington Post, there are arguments for state-sponsored journalism. Here’s my question: Should local authorities be asking for powers – and the ability to raise funding – to offer subsidies for responsible independent newspapers?

Can this be done in a way that ensures independent reporting?

Transparency for lobbyists

Like a minority of people who have watched what will surely be 2009′s official leitmotif - the demand for full disclosure from MPs – play out, I’ve wondered when similar demands will be applied to those who rival MPs for power.

This phrase of Larry Elliot’s – explaining the roots of the current economic crisis – underline the problem here:

“But there is a motley band of discontents for whom business as usual, in whatever form, means that another crisis will erupt before too long. They argue that the exiguous nature of current reform proposals is explained by the institutional capture of governments by the investment banks, the world’s most powerful lobbying groups.”

Certainly, politicians have been teed up so that they can be whacked squarely whenever they get ideas above their station. Right now, it would be hard to make the case that MPs are the right people to take on Tom Wolfe’s over-powerful Masters of the Universe.

In the same way that the Ross-Brand affair was used to tee the BBC up by politicians who don’t wish the corporation well, there’s an argument that demands for transparency rarely come from an organisation’s friends.

Much of this has been led squarely from the political right. The Taxpayers Alliance and a range of right-wing anti-BBC bloggers have worked in tandem with media owners that have been frustrated with what they see as the BBC’s anti-competitive influence on the media landscape. Certainly, at this moment, the libertarian right is the key mover behind the UK’s anti-politics campaigns on MPs expenses for reasons that have more to do with a pro-direct democracy position than more short term party political advantages. The current scandal has, after all, hurt the Conservative Party as well as Labour.

It’s hard to seperate this question from the differing political attitudes to the decline of newpapers. In no less a place than The Washington Post, we see this:

“For the first time in American history, we are nearing a point where we will no longer have more than minimal resources (relative to the nation’s size) dedicated to reporting the news. The prospect that this “information age” could be characterized by unchecked spin and propaganda, where the best-financed voice almost always wins, and cynicism, ignorance and demoralization reach pandemic levels, is real. So, too, is the threat to the American experiment.”

From the left, there appears to be an emerging response. The first is to harass the newspapers, those who use the libel laws to suppress inconvenient truths and other pedlars of perverted science. Jan Moir, Trafigura, and the British Chiropractic Association have all felt the sharp end of this kind of crowdsourced hostility in recent months. Read the rest of this entry »