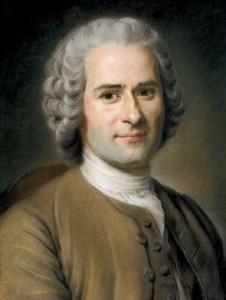

Jean-Jacques Rousseau: One Swiss national who probably would have been a bit annoyed by the Minaret ban.

The recent outcome of a Swiss referendum in which a majority have voted in favour of a minaret ban has helped to highlight a few important issue around the question of direct democracy.

Dan Hannan says that – while direct democracy is a great idea, this particular result is regrettable.

Make of that what you will. For me, the more interesting point is Chris Dillow’s return to his advocacy of Direct Democracy. He starts with a point that is, I believe, instantly problematic:

“There’s a conflict between liberty and democracy.” The Swiss decision to ban minarets illustrates this perfectly.

That’s too strong. As Norberto Bobbio argued, there is “a dialectical interplay between liberty and democracy.” But conflict? Only when you get an unmediated vote in which the majority get to impose their will upon a minority.

There is, undoubtedly an actual full-blooded conflict between liberty and the outcomes one could expect from the crudest forms of direct democracy. But the contrast between liberty and what Anthony calls ‘the larger view of democracy’ is less clear – indeed I’d argue – as Anthony does – that the larger view of democracy is the most effective guarantor of those liberties that Dan Hannan claims to be so fond of.

A while ago, Conor Gearty illustrated why democratic ‘impositions’ are clearly preferable to the tyranny of structurelessness that Dan Hannan generally advocates:

“…early democrats knew the value of government and well appreciated how the most resistant to regulation were those whose wealth and privilege were likely to be reined in by proper democratic government. To camouflage their self-interest in morality, these forces of conservatism described themselves as libertarian, in other words as committed to freedom and on that account opposed to governmental intrusion into their lives.”

… and

“If we fetishise individual freedom at the expense of our wider struggle for transformative change, we play into the hands of the right who use libertarianism as a shield with which to resist change.”

In many cases, the advocacy of crude direct democracy is simply a populist cloak for deep conservatism – or worse.

Chris Dillow’s arguments are, however, a good deal more sophisticated than ‘one-vote-per-person-on-everything’. He’s very keen (keener than I am!) on the idea that democratic decision-making often results in bad decisions. Instead, he advances the possible solution of demand revealing referendums. And Shuggy has taken issue with his ideas at length and has too many arguments against the proposition to list here.

I’d not dismiss this idea as quickly as Shuggy does though, for a number of reasons.

Firstly Shuggy is right: It’s an untried, undetailed argument with a few obvious flaws. I can’t imagine that it is a workable idea. But representative democracy has flaws as well. My hasty round up includes….

- Five years is a long time to be bound by one decision

- Emergence of remote elites – often almost a caste with various inappropriate biases

- Five years allows organisations to consolidate and monopolise – to create huge entry barriers

- Groupthink

- Crude trade-offs forced by political parties

If you lose the term ‘referendum’, demand revealing exercises may not be a bad idea. You don’t have to fully buy into the Wisdom of Crowds thesis that a large number of ironically detached stabs at a correct answer result in better judgments than those made by experts. You only need to go as far as the Clay Shirky-ish assertion that the knowledge outside your organisation is generally greater than that inside it.

It is in Burke’s often-overlooked notion that an elected representative should be in “the closest correspondence, and the most unreserved communication with his constituents” that I think that new communications tools offer the greatest possibilities. There are reasons that representative government is the least worst option open to us. Our politicians understand trade-offs and they get together to get a more complete picture of a problem. New communications tools mean that they can involve us – and be seen to involve us – in doing all of this more effectively.

I’d suggest that, in reaching for an alternative to representative democracy, it looks to me as if Chris is actually acknowledging that direct democracy will only work if it approximates what representative democracy does while avoiding some of the flaws. Surely it would be easier to switch the argument round and say that some of the more creative direct democracy tools could overcome the flaws of our current system?

Today, politicians could actively solicit detailed descriptions of the problems that they want to solve from the general public. A partnership with the people rather than purely delegated responsibility for five years. The semantic web is gradually grappling with the question of how people may be prepared to collaborate to describe problems and propose solutions and there are dozens of emerging applications such as Google Wave, MixedInk, and Debategraph to name but a few that are beginning to try to crack this nut. It’s a long way from leaving the geeky-ghetto, but the day will come.

And there are a number of reasons why this is so exciting. Because – unlike the use of focus groups – its not about mapping our sensory perceptions in order to sell us a bill of goods. It’s about presenting us with a structured set of trade offs – what do you really want more? This or that? And how much more do you want it?

In the late 1980s, I remember looking at a survey of public attitudes in the Irish Republic and found that the cost of phone bills was a matter of acute concern while the partition of that island was one of acute indifference. It taught me more about Irish nationalism that a bookshelf of Tim Pat Coogans.

Also, it breaks the dominance of the mass media. You can reflect a package back to people and say (as Microsoft laughably are trying to do at the moment) ‘You made this.’

Unlike petitions, participatory budgeting creates processes that politicians can ride along with – rather than be steamrollered by. They genuinely learn something from it – it’s not a process that is gamed by pressure groups and busy-bodies. But – and here is the most exciting bit – if politicians can crowdsource this judgment directly from the public, there is a chance that it could revive good old partisan politics.

At the moment, public judgment is provoked and marshaled in a slightly demagogic way by the media. We have a range of poles that few of us would recognise in our own circles – the mushy even-handedness of the BBC, the shrill reaction of The Mail or …. well you get the picture. The media focus upon general concerns. My newspaper is always full of the coverage of international football and the big clubs- England, Man Utd, Chelsea and Liverpool. Never the coverage of Nottingham Forest, D*rby County and Fester Leicester City that every cell in my being yearns to read.

Similarly, the mediated politics that dominates public life focuses on abstractions and issues that people actually hold relatively lightly in their own scheme of things. If politicians were dealing with us more directly – understanding our real interests and being able to challenge and respond to us in a direct way – surely a new set of political contours would emerge quite rapidly?

When politicians can say to us ‘we asked people like you to think about this problem and describe it to us’ or ‘we asked people like you to tell us what their priorities are’ elections could become more transparent and meaningful again. In government, of course, MPs will always seek to demonstrate their willingness to represent all of the people. But elections should be about the resolution of social tensions.

Finding sophisticated ways of involving people in supporting decision-making processes can reinforce representative democracy – not challenge it.

A blog about representative democracy, social media and a conversational politics. How will peer-to-peer communications change local democracy? How is representation changing?

A blog about representative democracy, social media and a conversational politics. How will peer-to-peer communications change local democracy? How is representation changing?

If ‘democracy’ means anything, it means not having to agree with apologists of the naked pursuit of power.

So the people dont want minarets? Too bad, swallow it up, because if you think the present representative democracy is working better, then explain how Blair got away with the Iraq war, how cheyney allowed torture as a means of PR, and so on?

And btw, todays front-line state is fully equipped to allow ‘direct democracy’; we have the technology, we have BB, the net, and too much tv to be good for us.

Dont you hate it when quangos monopolise far more than their share of policymaking? Dont you think people only enter politics seeking a way of making money? Do you think PR will come soon? Ha!

So its ‘crude direct democracy’ ? it still seems a better way of making policy than the one where ‘PM’ goes into room with ‘Pres’ and they agree to violate another country’s citizens ‘cos, well pres was the representative democrat wasnt he? And what about the impossibility of getting your ‘representative’ to eg vote against war?

And if you poll a countys citizens and they want the death pen, too bad for your liberal sentiments, thats democracy. We might even find citizens will educate themselves in some of the issues of the day and actually participate rather then thinking all polititians are gr**dy w^&*ers.

So you’d prefer Direct Democracy to our current settlement then?

Try California! https://localdemocracy.org.uk/2009/09/18/too-much-democracy/