This is the first in a series of posts on the subject of ‘How the semantic web can crowdsource high-quality judgment and improve policymaking’ that Paul introduced yesterday.

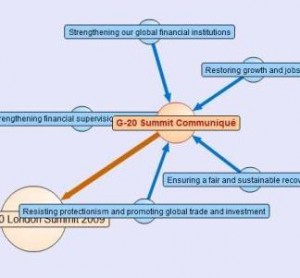

With all the talk about brand new crowdsourcing platforms, and letting the population ‘speak their minds‘, it’s easy to forget the mass of already-expressed opinion that exists in electronic form, and that can inform future debates. Not only the millions of overtly political blogs, but regular blogs, online newspapers, Wikis, and visual debate-mapping tools, like Debategraph.

Billions of individual thoughts and personal experiences have been written about, from all conceivable perspectives. No policy process is likely to come up with ideas that have never been thought of before; so expressed opinion represents an archive – a knowledge base – that should not be ignored. Here’s why:

- It already exists – the mental work has already been done.

- It happened – it’s a record of what happened when particular policies were tried.

- It’s not just blogs: thanks to TheyWorkForYou, Hansard reports and transcripts of Select Committees make for highly-detailed content.

- It can be linked-in: it can be dynamically matched, linked, and related to brand new policy debates.

- It can be made fresh – it can be given a new lease of life when updated collaboratively.

- It’s as good a source as any – basing arguments in brand new policy debates around what happens to be current in the mainstream media will inevitably produce less diverse, more error-prone, and less extensively scrutinised results than using sources that have already been run past potentially hundreds of human brains.

- There may be no alternative – it enables, and bootstraps new policy debates, bringing in the words of those who haven’t yet joined – or even heard of – the new platform.

The challenge of using technology to make sense of all this political information is what concerns us now.

My new project – Poblish.org – aims to put this content to use, and to collapse the distinctions between the worlds of blogging, collaborative editing, and debate mapping. The result will be a collaborative ‘open data’ platform that works for both bloggers and policy-makers, and that will nurture an ecosystem of new political data tools. Hopefully the Labour-themed iPhone app Paul mentioned yesterday will be merely the first of these.

I will be explaining more about Poblish in future posts: the particular problems it was designed to address, the questions it tries to answer, and more about how it can improve policy-making.

I like the idea of using stuff that has been written already (often without any intention of it being written to consciously contribute to a policy process) to be attractive on a number of levels.

1. It is more ‘admissible’ as evidence. In a courtroom, evidence has to pass a test before it’s introduced – what is its provenance? Who introduced it, and why did they look in the place that they did to find evidence that they are introducing. Content that is introduced into a process in this way is unlikely to be ‘inductive’ – produced as a wily response to a threat. It is likely to be honest and it’s more likely to be ‘disinterested’

2. It is more detached – you are likely to pick up more mild preferences and observations that can be weighted by others. So many peices of evidence that appear in articles, blog posts or research papers are there because they point to a pre-determined conclusion – ‘policy-based evidence making.’ By extracting a bunch of observations in this way, you are possibly ‘pre-populating’ an argument with lots of stuff that wouldn’t appear normally because it doesn’t lead to a neat conclusion.

I would say, however, that this is a complimentary activity rather than a standalone one, surely?

[...] believe that tools like this are an essential part of making the political blogosphere a knowledge base, that can not only improve political blogging, but also improve [...]